As the Chesapeake Bay blue crab population continues to struggle, what can we expect for life on the salt marsh?

The Chesapeake Bay blue crab population has plummeted to its second lowest level since 1990. Is the marsh, and coastal culture, also at risk?

This article is part of a larger body of work on the future of the American salt marsh. If that resonates with you, please subscribe.

Every year, around mid-July and during the week of my birthday, I prepare a seafood cookout. It’s something that I’ve done for at least the past decade, and in that time, it's evolved from a simple feast to a cherished tradition.

On the day of the cookout, I take whole menhaden and chop them into thirds. For those of you who don’t know, menhaden, or bunker, are nasty fish. They ooze a rank, amber grease that has the consistency of vegetable oil and it stains the skin with such potency that it seems almost immune to soaps, showers, and hand scrubs.

When you dunk that grease into water, it tends to form a slick, and that makes menhaden the perfect crab bait.

I cram the menhaden parts into a five-gallon bucket and leave the lid off to let it bake in the sun. As the fish-chunk-medley brines in its own juice, I amass a tower of collapsible wire traps on the flooring of my fiberglass boat. I fill the gas tank, check the motor, load the bucket, and, finally, set off.

Days where the summer heat curdles the salt marsh air are the best. On a day like that, my wife gets excited, because she knows I’ll return home in just a few hours with a bushel full of blue crabs.

I have another blue crab feast planned for my 31st birthday. It’ll happen in just under two months. But recently, the Chesapeake Bay’s 2025 Winter Dredge Survey had me wondering if I should arrange a back-up plan.

The Chesapeake Bay blue crab population has plummeted to its second lowest level since 1990, according to the survey. The number of spawning-age female crabs dropped by 18%, 133-million to 108-million, while the total tally of adults dropped by almost 50

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) released an immediate statement. They urged Maryland to consider stricter enforcement of female crab harvest and in particular, called for restrictions on sponge crab imports from Virginia.

Sponge crabs, female crabs bearing a mass of eggs on their abdomen that looks like a swollen orange sponge, are illegal to harvest in Maryland for obvious reasons. On the other side of the Chesapeake in Virginia, however, sponge crabs are fair game.

The CBF also pleaded with Virginia to reduce its total blue crab harvest. Both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency, they say, need to be fully funded by the federal government. Both agencies play a critical role in managing blue crab habitat.

The impacts of the shrinking crab population became immediately apparent in my hometown over Memorial Day Weekend.

My wife and I went out for lunch at a semi-boujee seafood restaurant in Cape May where we were seated at a prettied up picnic table, painted all white down to the splinters under a beet red umbrella, situated near the railing of an outdoor patio.

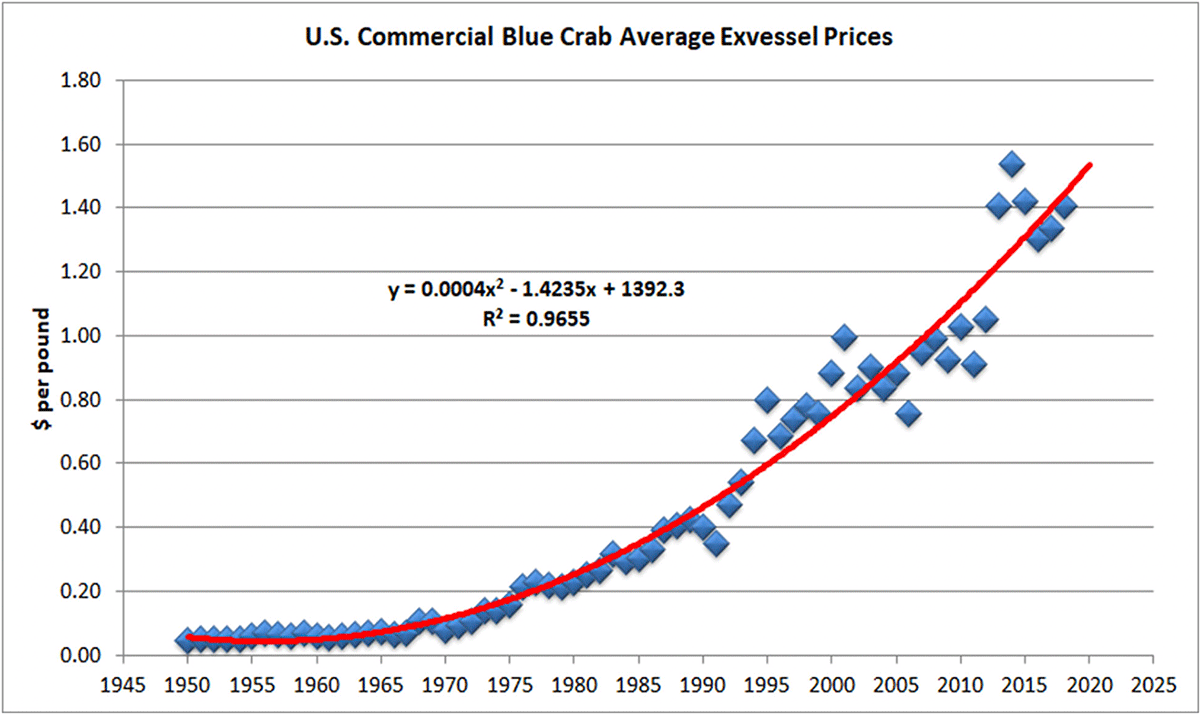

A smooth breeze carried across the marsh and mixed with the spicy scent of Old Bay seasoning that poured out of the kitchen. Our hunger grew ravenous. When our waitress handed us two laminated menus, I traced mine straight to the blue crab specials. Three crabs, I learned, would cost over $30.

I carried that information around as if it were an insult.

Thirty bucks? How in the hell could three crabs cost over 30 bucks?

Initially, I thought it was a shore town scam- up-charged seafood meant to drain the pockets of coastal tourists. Later, after my frustrations had stewed into conspiracy theories, I discovered the Winter Dredge Survey. To figure out what was going on, I embarked on a deep-dive into the Chesapeake Bay’s blue crab industry.

New Jersey has a healthy commercial crabbing industry, but I learned that my home state’s commercial harvest pales in comparison to that of Maryland and Virginia.

The commercial blue crab harvest in the Chesapeake Bay region averages around 60-million pounds a year. Meanwhile, the combined commercial and recreational crab landings in the Delaware Bay reach just a paltry 10-million on a good year.

To match the seasonal demand for blue crabs and combat low supply, New Jersey does what most states do: import them, mainly from the Chesapeake, and raise market prices.

This all explained the price of crabs on the menu, but it didn’t explain why the blue crabs struggle.

In the Chesapeake Bay, I learned, blue crabs combat myriad threats, and most of them are from us.

Nitrogen and phosphorus leach from surrounding farm fields and drain into the bay from its tributaries, causing algal blooms that destroy water quality. Eelgrass, the chief benthic grass of the Chesapeake, forms verdant underwater fields when its population is healthy. When the eelgrass fields grow thick they provide refuge for blue crabs, but the bay has lost 29% of its eelgrass coverage since 1991, mostly due to rising water temperatures.

Invasive blue catfish, introduced to the estuary in the 1970’s by none other than the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, also whittle the blue crab population.

While all these threats pile against the blue crab, the cause for the recent decline remains unclear. Likely, it’s some combination of all these threats, or something new (although Maryland DNR suggests it could be from a harsh winter season. That reasoning, to me, reads like a low-hanging theory).

The true cause of the decline is expected to be determined with the release of an updated stock assessment report, which will be published in March of 2026.

Beyond the scientific data and management mishaps, my deep-dive made me realize two important things. Number one, the salt marsh is as resilient as it is fragile.

Heralded as the most productive ecosystem on Earth, the salt marsh is elastic. It’s pliable. It can be stretched and scoured and flooded and drained and still operate the way it’s supposed to. Belonging to neither the land nor sea, the salt marsh lies somewhere in between.

It sequesters carbon from the atmosphere and filters pollutants from the ocean. It supports marine mammals and fish, land mammals and even birds and reptiles. It’s a fecund landscape, an engine rich with life and productivity that all becomes apparent through the sulphuric fumes that season its low tide smell.

With such robust biodiversity, the marsh, in a way, protects itself. Organisms ranging from the microscopic to the great blue heron interact and through their connections form a gigantic shield of armor. Complex food webs, systematic nutrient recycling, and seasonal rhythms of life and death guard the marsh from extinction. The nuts and bolts holding that armor together are the blue crabs.

Here’s what I mean.

Blue crabs feed on periwinkle snails, and the periwinkle snail’s favorite food is Spartina grass. Without blue crabs, periwinkle snails trim fields of Spartina grass down to mere nubs. In marshes without Spartina, endangered salt marsh sparrows can’t nest and small fish like minnows can’t hide. River banks wash away as the roots of Spartina dissecate.

In a healthy marsh, the roots of Spartina reach deep into the soil and form an interlocking twill that stabilizes stream banks and prevent them from erosion. Without Spartina as its anchor, the salt marsh becomes consumed by the sea and its ecology dies. In that way, blue crabs are the ones that hold it all together.

For all its resilience, however, the essence of a salt marsh can be gutted. I’m talking about its intrinsic value. It’s spirit.

Salt marshes can creep inland, but what if the swelling ocean swallows the creek you fished on as a kid?

Salt marshes can soak up pollutants, but what if we dump so much fertilizer in the water that it overwhelms the system and starts killing the eelgrass beds?

What if the blue crabs disappear?

A landscape that has lost its soul is hardly the same as the original. And that thought led me to my second epiphany: how grateful I am for my birthday cookout.

Somewhere in that yearly tradition, I discover the soul of the marsh. I eat crabs just the way my dad did and his grandfather before him. It ends up something like a communion. I sit at a round glass table draped in newspaper as the summer sun throws heat through my back porch screen. I watch hoards of strawberry flies hover in the yard as I fill ice cold water into my dog’s bowl so that he can keep me company.

He looks at me from the floor, panting, as I crack, break, and pick my way through a pile of crabs. The front claws are succulent and sweet. The meat of the body is tender and briny. My wife likes to dip claw meat in melted butter. My great grandmother likes to chew on the legs from bottom to top, gnawing her way up the shell until the meat spills out like toothpaste.

I prefer my crabs doused in Old Bay seasoning and coated in vinegar. Prepared that way, I can sit at a glass top table for hours, reflecting on my childhood and the way the hum of an outboard motor bounces off river banks, simultaneously feeling invasive in such a landscape I love for its quietness yet in some perverse way filling me with joy.

I can sit at that glass top table for hours, with the smell of warm grass and hot butter and white vinegar, the way my mother-in-law and I did last summer, when we huddled around a pile of crab shells and talked about relationships and how hard it was for her to bear the loss of her mother and father.

We picked crabs to the tune of soul music on the oldies radio and talked our way through the beauty of family. When we had a big enough pile of meat, we made crab cakes.

Memories of birthdays past bring me back to sunburnt skin and fingers pruned by crab juice; that infusing smell of bunker grease.

I can sit at that glass top table for hours where I think about the marsh.

This year's Chesapeake Bay blue crab survey sent alarm bells ringing through marine conservation corners. But blue crabs are far from imperiled. And that’s a good thing. It’s settling to know. Because as long as the crabs are on the marsh, they’ll end up on my glass top table every summer, and that will mean that I have been on the marsh too.