Blue Crabs by Dawn

Blue crabs offer an easy avenue to explore the summertime salt marsh. The best part is, they taste good too.

If you’re going to get pinched by a blue crab, pray it's by the left claw.

Admittedly, both claws hurt like hell, but the left claw is usually weaker and used like kitchen shears. It’s slender, fine-toothed, and a bit more brittle. It’s the cutter. Their other claw, the crusher, packs the punch of a weaponized anvil. It clamps with so much force that it can shatter otherwise impenetrable shells, like those meant to safeguard snails, clams, and oysters.

One researcher measured its force. At low tide throughout the entirety of his senior year, Drew Martin, a biology major, collected blue crabs from the seagrass beds that surround St. Teresa, the Florida town home to Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Laboratory.

He noted that when he put the crabs in holding tanks, they often tore each other apart. He recorded ripped limbs, pierced shells, and cannibalism. Where there wasn’t violence, there was sex. Drew caught the deed twice, each time when a female molted- the only time a male blue crab has a chance to breed her. The gore and affection became so intense that, in order for Drew to actually commence his study, he had to separate the crabs into individualized compartments.

Drew antagonized each crab to use their crusher claw and pinch a homemade bite force transducer. Thats the fancy name for a scale used to measure the biting power of an animal. The transducer, crafted by a previous student in the lab, has two plates. Each plate is about the size of a domino and they lay parallel to each other. When they compressed, a force gauge sends a measurement to a digital display screen. One crab pinched the dominos and pushed the display to its limits. It recorded a force of 291.62 Newtons.

To get pinched by a crab like that would be like laying a serrated knife on your finger, then dropping a 65 pound boulder on the blade.

I’m thinking about Drew’s research as I lean over the gunnel of my boat to scoop a handful of brackish water. I can’t find my reflection in the river’s current. It runs chocolate-brown, rich with the sediments and detritus that create a productive marsh. Clapper rails sing from the banks in a series of cackles. Each note drops quicker than the one before it, like the accelerated bounces of a dropped ping pong ball. Seagulls pick at fiddler crab carcasses and erupt into an occasional frenzy. The sun makes the reeds glow but its UV radiation slow cooks my skin. A little blue heron flushed from the cordgrass when I turned up this river. Now its current is dotted with buoys, each attached to a wired crab trap. I rub my hands together, kneading brackish water between my palms so vigorously I can almost feel the salt grains, but I still can’t shed the slime, or the smell, of bunker grease.

Crab diets look a whole lot like how mine would look if I preferred my food uncooked and alive. They eat fish. A bunch of fish. And bivalves, like clams and oysters. Sometimes, shrimp. Above all else, crabs carry a lust for the dankest, greasiest, and fattiest of foods. Bunker top that list.

Bunker, or menhaden, have many uses. Native Americans used them to fertilize fields. Their young of year get threaded to fishing hooks to tempt migrating striper. Whole pods are netted off the coasts of the Carolinas and brought to factories, where their limp bodies are pulverized, squeezed, and juiced for their oils. Those oils end up neatly packaged in fish-oil pills. The labels promise to extend your life.

Earlier that morning, I chopped a dozen bunker into thirds - head, midsection, and tail- and loaded the parts into a perforated bucket. I wedged the bucket in the cockpit of my sneakbox beside a stack of wire crab traps and a cooler. Then, I threaded a paddle into the little cockpit space that remained and laid a crab net beside it.

Somehow, I managed to wriggle in, twist the throttle, and set all the traps, landing me here with , river-water-wet hands that fail to hide the acrid stench of the bunker. From my seat on the cooler lid I can see the braided tire cords that pass through the eyes of eight buoys. The buoys are laid into a line just off the main current of the water. The cord sinks from the buoy all the way to the creek bottom, where it attaches to a short string that splits into four. Each of those four smaller strings attaches to one of the four walls of the wire crab trap. Without tension, the trap doors fall open like a castle drawbridge lowered over a moat. Yank on the cord, however, and the drawbridges retract, trapping the crab in the castle. It’s a citadel trotline.

When you’re checking traps like this, you want to do it against the tide. Currents pull on the cord, and if you rip up the buoy with the tide, the trap ends up underneath your boat, hitting the hull, and potentially opening the doors. I check the traps in a quick sweep. The first run yields three crabs. The second, two. It’s a slow day. On the next run I pick up my first two traps and set them beyond the last one. Each subsequent run, I’m moving traps, picking my way up the river.

Crab boils tend to start this way - an early, briny, sun-scorched morning, coffee-coated tongues and the smell of dead fish on a boat. If you’re lucky, it includes a few crabs, but sometimes, you need to work for them. The work pays off when the crabs get added to a stainless steel crockpot cradling one inch of white vinegar and a few more inches of tap water.

Blue crabs turn red when they’re ready to eat for the same reason that flamingos are pink. It comes down to a pigment called astaxanthin. Flamingos get the pigment from the shrimp they eat. Crabs get the pigment from their food too, but they bind the pigment to a protein in their shell. That gives the crab a dark green, only sometimes reddish, appearance. Cook the crab and the protein flies from the astaxanthin. All that’s left is red.

New water proves productive as my cooler fills on the next couple of runs. One crab looks redder than the others, and I begin to wonder if it has some unbound astaxanthin floating around in its shell. Another has a rusty belly that gives it the look of a grimy bathtub - a clear sign that it’s been a while since the crab has molted. Crabs like these are chock-full of meat.

My second to last trap yields an oyster toadfish. I remind myself that NASA launched one of those suckers into space. I’ll never get over that one. Then, finally, my last trap yields a short. I shake it from the trap over the gunnel and watch it plummet to the water. When it lands, it keels over like a sinking frisbee, then catches itself, turning on the thrusters of its paddlefins, darting into the chocolate.

As I leave, I reflect on the past summer, knowing this will probably be one of my last crab outings until 2025. Duck season is just a few short months away. The sneakbox will be draped with grass and adorned with a sprayshield. I’ll man the motor while Boone, my field golden pup, sits between my legs. If we’re lucky, we’ll have some ducks, and odds are, we’ll be hunting up the same crick I’m crabbing. The sun hangs in the middle of the sky as I motor home. The river banks reveal themselves to the dropping tide. Yellowlegs wade through the mud. But we both know it can’t last long. It'll be all blue crabs by dawn.

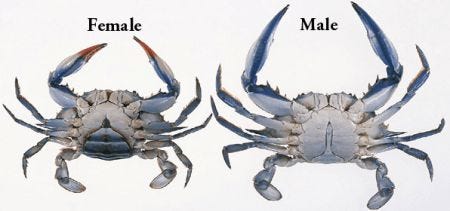

Crab Nomenclature

Jimmy - Male crab. Mean sucker.

Sook- Female crab. Still a mean sucker. Sexually mature.

Sally- Immature female.

Apron - Sex organ on crab belly used to tell sex.

Sponge- Female with eggs bursting from their apron.

Doubler- Jimmy cradling a molting sook. This is when they mate.

Peeler- Hardshell crab about to molt.

Softshell- Crab post molt, before the shell hardens.

This was a delightful story that made me hungry. Well written.